Guest blog: How we got to 20 Years No Kill, part three with Robin Starr

Editor’s note: This is the final post in a three-part series, find the first and second installments.

Like most successful social movements, the no-kill movement has matured and broadened over the years since its inception in the 1980’s. Initially, “no-kill” meant only that the killing of healthy homeless animals in shelters would be eliminated. The pets that were guaranteed to be saved early in the movement were often called “adoptable” meaning that they were already sufficiently healthy and well-behaved to be suited to being a pet in a home. Committing to save all of the healthy or “adoptable” animals was definitely a step forward over the massive killing of healthy animals that had prevailed in prior decades, but it was still the relatively easy part.

Saving expanding categories of homeless animals

As many of us in the no-kill movement thought more deeply about its tenets, we recognized that we also must save the life of every sick or injured animal if veterinary care could return that animal to a life of quality. In other words, only true euthanasia — meaning ending the life of an individual whose condition is not treatable and who is suffering — should be permissible under valid no-kill principles. These principles also required that the numbers of “feral” cats (which we now call “community” cats) would have to be managed in non-lethal ways. Subsequently, we came to recognize that animals with chronic but manageable ailments like diabetes must also be saved. With time, we also saw that animals with problematic behavioral issues that could be modified or managed such that the pet could live a good life in a carefully chosen home also must be saved. This latter recognition was largely due to the victims of dog fighting at Bad Newz Kennels, who were the first ones to be saved from conditions of terrible fighting abuse in 2008, rehabilitated and adopted to carefully chosen homes or cared for long term in sanctuary.

Enlisting community support

It was a tall order because these categories of animals — the treatably sick or injured, the chronically ill, and the behaviorally challenged — were much more expensive and time consuming to save than were healthy pets, but it was clear to us that they must be saved if we were to be true to the no-kill tenets. In order to save them, we had to provide many more programs and services to our communities, but first, we must shed the long standing mindset in the animal welfare field of distrusting the public. The old school view was that people could not be trusted to be caring and responsible to pets. Therefore, they must be able to relinquish their pets to a shelter at any moment and they must be subjected to intense scrutiny before being allowed to adopt (even though the pet was likely to die if not adopted). To make communities no-kill, we would have to enlist the active help of the people there to save animals and that meant we had to educate and then enlist their aid to help us and trust them to be compassionate.

At each stage as no-kill evolved, the Richmond SPCA provided our community with the programs and services it needed to meet this expanding commitment and engaged our community as a true partner. We got rid of intrusive adoption practices that bore no evidence of actually improving adoption outcomes for pets. We asked people to help us by fostering underage kittens and adult animals under treatment for medical issues. We educated people about feral cats and asked them to be caregivers for feral colonies. In general, they responded willingly and generously.

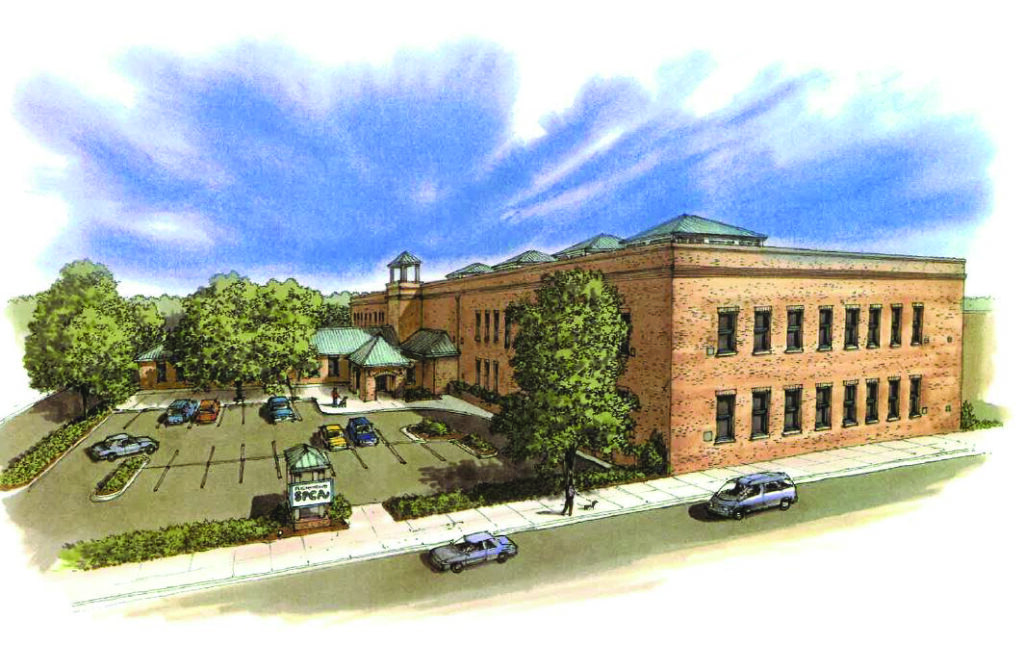

A new home to house new services

Our original no-kill commitment would clearly require massive spaying and neutering, humane education for our community and more effective adoption programs in partnership with the public shelters. We badly needed a larger and more progressive facility that could house a surgical suite, a healthier kennel environment, spaces for humane education for adults and kids and more welcoming adoption areas than the 1960’s building on Chamberlayne Avenue could provide. I looked at possible structures all over the area until, one day, I found an old tobacco warehouse building on Hermitage Road for sale. The building had been renovated in the 80’s by Richmond Memorial Hospital. It required a huge amount of work for the building to meet our needs but the price and the square footage were right and the zoning would allow us to operate a shelter there. After long negotiations, we bought the 64,000 square foot building for about $1 million.

To pay for the purchase, renovations and increased operating expenses, we ran a capital campaign with the support and leadership of Claiborne Robins. We moved into the new building in 2002 and opened Smoky’s Spay Neuter Clinic where we performed a prodigious number of spay and neuter surgeries over many years (as many as 14,000 annually) which had the intended effect of greatly reducing the numbers of homeless animals entering local shelters.

We provided spaying and neutering and rabies vaccination without charge to the wonderful people caring for feral cats and we worked to educate and convince the community to live with feral cats compassionately.

It became clear that a crucial element of reducing the number of homeless animals entering shelters was keeping pets in good homes they already had and that meant working through behavioral challenges that made some pets hard to live with. So, thanks to the addition of the incredibly wise and capable behaviorist Sarah Babcock to our staff, we could provide behavioral consultation with a high level of expertise to people who were experiencing behavioral challenges with their pets. and we could bring into our care from other shelters animals whose behavior was less than ideal, provide behavioral rehabilitation and safely place them in good homes.

Expanding transfers beyond Richmond

As the public shelters in our community over time became more progressive and more committed to saving lives, they needed our help less. Similarly, we were gratified that the community developed a number of other capable spay/neuter clinics. This progress allowed us to shift our resources away from doing so much spaying and neutering and focus more of them on providing medical and surgical care to the sick and injured animals that were usually the first to die in shelters across Virginia, broaden our reach across the state and even save animals in other states. This effort remains our focus now.

Making veterinary care more accessible

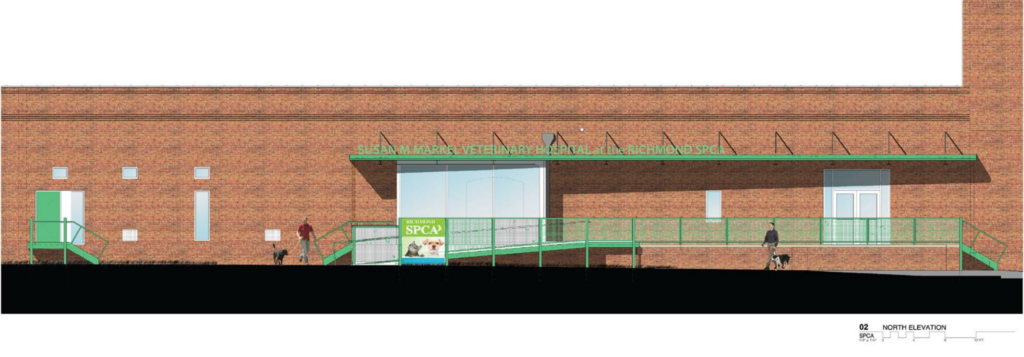

The last and probably most important step in our giving our community the tools to become no-kill was to provide access to high quality veterinary services for people of limited means. To end the loss of life in shelters, it is crucial that people of all levels of affluence be able to adopt and retain their pets. Veterinary care is often a major stumbling block to that goal. So, we raised the money to create and operate the Susan M. Markel Veterinary Hospital to provide care to the pets of people who could not afford that care otherwise and who, without it, would be likely to refrain from adopting or to relinquish their pet at a shelter. The fundraising for this service was very long and hard but we opened the hospital in 2016 and it has made a huge life-saving difference for so many pets and the people who love them.

Matthew Scully wrote, “When we shrink from the sight of something, when we shroud it in euphemism, that is usually a sign of inner conflict, of unsettled hearts, a sign that something has gone wrong in our moral reasoning.” The no-kill movement recognized this fact in the massive killing and callousness that defined our sheltering system in the 20th century and we worked to right a terrible wrong. That work is not finished by any means but we have come a very long way with much to celebrate. I am eternally grateful to have played a role in this progress for the animals we love.

Robin Robertson Starr is a current member of the Richmond SPCA Board of Directors. She served as the organization’s chief executive officer from 1997 to 2019. Robin is now enjoying retirement along with her husband Ed and a home filled with Richmond SPCA alumni dogs and cats.